Barbarians, Banishment and Beauty: The Unlikely Story Behind Murano Glass

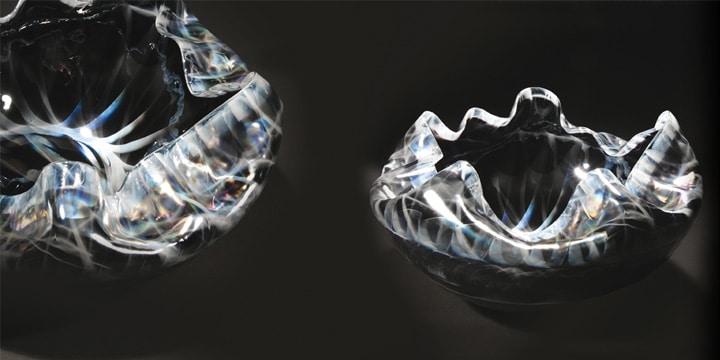

Native Trails is known for its one-of-a-kind products that seem to speak of extraordinary past. Having launched the handmade Murano Collection of glass sinks in partnership with artisans in Murano, Italy, Native Trails has most recently immersed itself in the history of Murano glass. It’s easy to get lost in the mystery behind this artform, as it’s every bit as intriguing as the glass itself. A bathroom sink with a story to tell? Indeed.

The journey to Murano

Venetian glassmaking originated some 1,500 years ago, when glassmakers from Aquileia, Italy, made the voyage to the Venetian lagoon to escape attacks by barbarians during the Roman Empire. Glassmakers who relocated from Byzantium and the Middle East further enriched the talent pool in the city. There, molded glass was affixed to the ceiling of lavishly decorated public bathhouses, providing illumination and delight. Additional uses for glass would soon emerge in the form of beads, mosaics, jewelry, mirrors and windows. While these products were widely exported, they were available only to the wealthy, as glass was then considered an extremely extravagant and valuable commodity.

By the eighth century, Venice was a leading location for glass manufacturing, and by the late 1200s, glassmaking was Venice’s primary industry. To outline regulations for the industry, a Glassmakers Guild was established. However, the Guild’s motives were questionable, as it also called for a law to be passed that would mandate all glassmakers to move from Venice to the island of Murano. Because glass factories frequently caught fire and the buildings in overpopulated Venice were mostly wooden, there was fear that glassmakers’ furnaces would ignite the city.

That’s how it came to be that in 1291, all glassmakers who lived in Venice were ordered to move to Murano, a cluster of seven tiny nearby islands connected by bridges. By cloistering the artisans away on Murano, their skills and trade secrets proliferated for centuries, so that it became the glassmakers’ wonderland that it remains today.

It’s worth noting that not all historians believe the theory that the glass artisans were relocated to protect them from setting fire to Venice. Many believe the true motive for this law was to isolate them so they wouldn’t be able to disclose trade secrets.

Not only were the artisans banished to Murano, but another law passed in 1295 that further forbade the glassmakers from even leaving the island. In spite of this, they were treated as the island’s most prominent citizens and enjoyed a heightened social status and lifestyle. Allowed to wear swords, they were protected from prosecution by the Venetian state, did not work during summers, and their daughters were married into Venice’s most affluent families.

With this isolation, the craft evolved, with many innovations and techniques originating in Murano. In the fifteenth century, Murano was known for cristallo—a fine, almost transparent glass—and lattimo, a porcelain-like milk glass. Then, for a time, the island was best known for its mirrors, then its chandeliers, also for its glass beads, and gemstones made of glass and many other varieties of glass. In 1450, a technological revolution marked the end of the middle ages and beginning of a renaissance, punctuated by glass artist Angelo Barovier’s discovery of how to remove impurities from soda ash to create clear glass. The secrets that spun out of the work of families like the Barovier family were regarded much the same as treasure. Fathers in glassmaking families even passed down to their sons zealously guarded glass-making recipe books.

During the 17th century, Murano glass entered a period of gradual decline, punctuated by Napoleon’s conquest of Venice in 1797 and his abolishment of all guilds, including the Glassmakers Guild. By 1820, almost half of the 24 furnaces that existed in Murano in 1800 had been shut down, and only five furnaces continued to produce blown glass.

Over many decades, the industry got back onto its feet and new, prestigious firms were founded. Murano’s glass craftsmen began to offer services that would restore old Venetian mosaics, including those at St. Mark’s basilica. After centuries of history and myriad challenges, the islands that comprise Murano, which altogether measures about 1.5 km (0.9 mi), are still today, synonymous with glass, and the glassmakers highly revered.

Murano’s beauty offered its residents no shortage of inspiration. Says historian Laura Morelli, “Murano emerges from the Venetian lagoon, a vast expanse of water whose surface reflects every shift in light. … Glassmakers observed these shimmering waters outside their workshops, a vision reflected in the art that has made Murano, and its glass masters, world-famous.”

Writes Morelli, “Even with the great variety of Murano glass techniques and its long history, there is something cohesive in the visual vocabulary of Murano glass. Even ancient pieces of glass discovered in the Veneto show that the region’s glassblowing techniques have remained consistent since ancient times. Some centuries-old museum pieces look remarkably contemporary, with the colorful stripes and swirls we still associate with Murano.”

Among many other prominent glass artists, Dale Chihuly was greatly inspired by Murano glass. During the 1970s, Chihuly even brought two Muranese masters to teach students at his Pilchuck Glass School near Seattle. According to Chihuly’s website, though, it was difficult to get the two glassmakers to reveal their closely guarded trade secrets. In fact, in addition to their glassmaking techniques, a long tradition of secret-keeping has been passed down through generations of Murano glassmakers.

To protect its unique history and reputation and help consumers identify authentic Murano glass, the Veneto region in 1994 began certifying Murano glass, to guarantee to the consumer the certainty of purchasing a product made on the island of Murano in Venice, according to the traditional techniques of the master glassmakers.

Few would dispute that the finest glass in the world continues to be made in Murano. Its glass uniquely represents the past and present, and Native Trails is pleased to be part of its future.

Learn about how our one-of-a-kind Murano Collection glass vessel sinks are made here, though parts of the process remain trade secrets to this day.